The conclusion of text-based negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2019 paves the way for the economies of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to strengthen their economic integration with five of its dialogue partners, namely Australia, the People’s Republic of China, the Republic of Korea, Japan, and New Zealand. The economic integration of ASEAN into its dialogue partners is a major milestone in the realisation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) that aims to integrate ASEAN into the global economy.

In this article, I argue that small changes in trade policy instruments under RCEP are likely to have significant impacts on trade flows in ASEAN. Below, I explain three key drivers in RCEP that can lead to the growth of ASEAN’s trade in goods. These key drivers include the comprehensive coverage of RCEP, the large market size, and the strong economic linkage via trade and investment.

First, RCEP covers comprehensive trade and non-trade issues that can enhance further liberalisation of trade and investment in ASEAN. It consists of 20 chapters, which extends the ambition of ASEAN beyond the limits of trade and trade policy, including non-trade issues. Some of these, such as rules of origin, technical barriers to trade, trade in services, electronic commerce and intellectual property, have been included in the AEC Blueprint 2025, but the RCEP is more likely to further in these directions than those of the AEC. In fact, ASEAN countries are implementing the Guideline of Non-tariff Measures to eliminate non-tariff barriers, but they have not yet made much progress in doing so.

Taken together, commitments made under the RCEP will benefit consumers and businesses in ASEAN by reducing unnecessary costs that can often be imposed on them by both, border and ‘behind the border’ trade restrictions, enhancing businesses to utilise preferential tariffs with a common rule of origin, and stimulating innovation with stronger protection of intellectual property rights.

Second, RCEP offers opportunities in the form of a huge market of US$24.8 trillion and over 2.3 billion people. In 2018, the combined gross domestic product (GDP) of RCEP (on a purchasing power parity basis) is greater than that of other trading blocs such as the European Union (EU) and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In Asia, the combined GDP of RCEP is about five times that of the members of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), and about three times that of other Asian countries, including India.

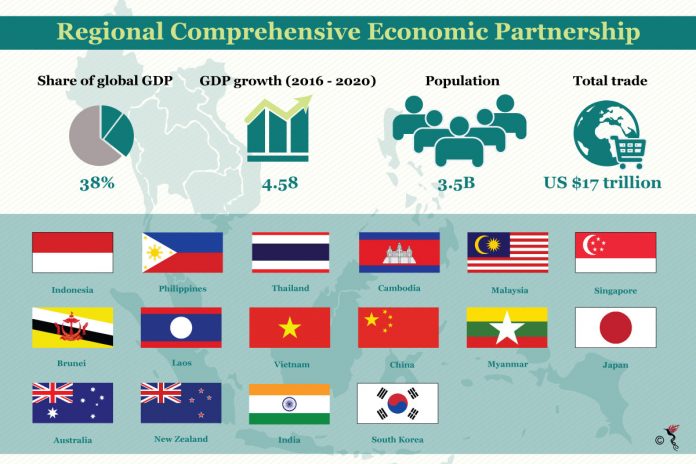

Source: CIA World Factbook 2020.

Third, ASEAN and its dialogue partners have a strong economic relationship through trade and investment. In 2018, ASEAN’s total trade in goods – i.e. imports plus exports – stood at US$2.8 trillion, 34 percent of which was accounted for by the bilateral trade between ASEAN and five of its dialogue partners and 23 percent was accounted for by intra-ASEAN trade. Moreover, total inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) in ASEAN recorded at US$152.8 billion in 2018 – 25 percent of which was sourced from its dialogue partners and 15 percent was sourced from ASEAN countries. Taken together, values of intra-RCEP trade and investment already accounts for 57 percent of total trade and 40 percent of total FDI inflows in ASEAN, respectively.

The large market size of RCEP coupled with strong trade and investment linkages between ASEAN and its dialogue partners suggest that any small reduction in trade barriers is likely to increase significant gains from trade. These gains will then translate into greater number of job creations, and hence resulting in an increase in GDP and reducing poverty in ASEAN emerging economies such as Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar.

To realise economic gains from RCEP, policymakers should ensure that trade provisions in RCEP are deeper than those in existing ASEAN Free Trade agreements (FTAs), namely AFTA and ASEAN+1 FTAs such as ASEAN-Australia and New Zealand FTA, ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership, ASEAN-People’s Republic of China Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement, and ASEAN-Republic of Korea Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement. For the case of AFTA, member countries identified sensitive sectors in which they do not fully eliminate tariffs, especially for rice. The more trade is covered by the sensitive sectors, the smaller are the economic benefits from tariff elimination under the FTA.

Although the full text of RCEP has not yet been publicly released, there are three reasons to believe that RCEP should be deeper than the existing ASEAN FTAs. First, RCEP should emerge as a region-wide regional agreement to consolidate the existing ASEAN FTAs and hence reducing the negative impact of complicated rules of origin on trade flows. Second, the threshold of tariff reductions in RCEP should be set more comparable to another regional FTA such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which aims for 99 percent tariff elimination. Third, the RCEP will also be an FTA, and it seems likely that the reductions of tariff, non-tariff barriers, and barriers to trade in services among RCEP countries will be more complete and more general than those of AFTA and the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs. The RCEP will also exempt some sensitive sectors for trade and investment liberalisation, but which sectors and how many of these sensitive sectors remain to be seen when the agreement is signed in late 2020.

Source: The ASEAN Post